Communicating Science

Written on 2019-03-25

“What can we do to communicate our research to the public?” This was the question for a discussion session with some of my colleagues last week. Many scientists see the need for this kind of communication, but few know how to go about it, and even fewer actively do it. After all, how do you explain your work on, say, a channel protein of the Venus Flytrap to your neighbour, and why should he bother listening? It is a challenge. But believing that it's worth the effort to try, here are some general principles we found.

Stepping out of the Ivory Tower

The first question we asked ourselves is: why bother? Why do we want to tell others about what we do? In most cases, one can get through a scientific career perfectly well without engaging the public. So why do we want to?

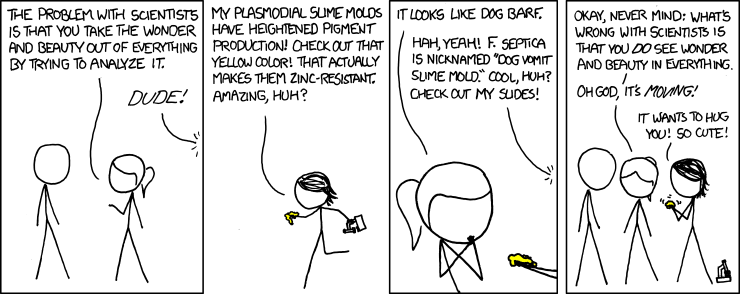

One big reason is to share the wonder. Every scientist I know loves his or her work and is awestruck by the intricacy of nature. This wonder is something we want to share; we want our friends to see something of the miracles we have discovered. Curiosity is one of our defining attributes as scientists, but we are not the only ones that are curious. And so when we talk and write about our work, we do so both to awaken and to satisfy curiosity.

We also want to share our lives. Few people have an accurate idea of what scientists actually do – not surprising, considering how widely this varies from discipline to discipline. One of the colleagues in our little circle is about to start a podcast addressing just this question; interviewing various scientists to show people what it's like to work in science. We think people have not just an interest but a right to know. After all, their taxes pay our salary.

Lastly, we want to share our knowledge. We dedicate our lives to the quest for knowledge; a great privilege that comes with great responsibility. Many of us are helping to look for answers to some of the most pressing issues of our time. From disease control to climate change and world hunger, our accumulated expertise is too valuable to be hidden away in some obscure journals. We may not have all the answers, but we have something to say.

Start with Why

The problem is that many scientists are surprisingly bad communicators. Getting lost in details before we've painted the big picture, and resorting to the most arcane terminology, we often lose even our fellow scientists. But if we are unable to capture our peers' attention, how will we manage with a lay person?

The most pressing issue here is really how to spark that initial interest. Motivation precedes communication; if your listeners aren't interested, nothing else you do or say matters. So how do you make them want to listen?

This is a fundamental problem of any public speaking (or writing), and it boils down to one word: connection. You need to connect with your listeners, and you need to connect them with whatever you're talking about. We don't like listening to people or topics we don't have any personal connection to.

Creating this personal connection is about building relationships and touching the emotions. Both are things many scientists are particularly bad at. Not only do we tend to have very rational mindsets anyway, our whole training teaches us to cut out any emotions and concentrate on the facts. And so learning to communicate effectively with outsiders will require us to learn a whole new skill: engaging the heart.

There are two main ways to do this, and both fit into what Simon Sinek calls “Start with Why”. The first is to create the connection between the listeners and the subject. For example, when I talk about my work on invasive species, I might tell whoever I'm talking to about the devastating economic and ecological effects of the zebra mussel in the Baltic and the North American Great Lakes. This is tangible, close to home and invokes an emotional response. I can then explain that I am trying to understand what factors are necessary for something like this to happen. As in any good story, I start with the conflict, the problem, and then work towards a solution.

The second option is to build the personal connection between listeners and speaker. Quite a few of my colleagues work on carnivorous plants such as the Venus fly trap. Understanding the molecular biology of its leaves isn't going to save the world, no matter which way you spin it. But it is fascinating, and that is exactly the approach you can use when talking about it. You could start by telling your listeners about this amazing plant that can actually count. Bringing across the excitement you have for your project is an excellent way of creating a connection to your listeners and piqueing their interest. Share your story, it's the best story you have.

In summary, the first thing you need to do is answer the Why? question. Why are you doing this? Why is it important to you? And why should it be important to your listeners? Connect with your listeners, and connect your listeners with your subject.

The Scientist's Grandmother

So you have your listeners' attention. But if you now embark on a lecture about the relative merits of Bayesian statistics, you will lose them as quickly as you got them. How do we manage to communicate science simply, without over-simplifying? Three tips to help you explain your work to your (metaphorical) grandmother:

“Keep it simple, stupid!” The old engineering adage applies nicely to the language we ought to use when talking about science. Technical terms are a neat shorthand, enabling us to succinctly express complex ideas when talking with other experts. With non-experts, we need to lose them. Another thing we need to lose are all those other high-sounding words we like to decorate our papers with. I dare say most of biology could be explained to a moderately intelligent twelve-year-old, if only one remembered to use simple words.

Use analogies. For anything abstract or not directly visible, try to find a fitting analogy from your listeners' daily life. Analogies are never perfect, but they sure are helpful. They're not always easy to find, though, and take practice to come up with. One famous analogy is Emil Fischer's “lock and key” explanation for enzyme-substrate interactions. Again, it's not perfect, but it has helped generations of students envisage a highly complex process taking place on minute scales.

Use illustrations. Analogies are word-illustrations, but real, graphical illustrations are perhaps even better. “A picture says more than a thousand words”, after all. As scientists, we are used to creating high quality graphics for our publications. This is a skill we can also leverage when talking to non-technical audiences. A good illustration can bring across a complicated concept in a single, visually appealing entity. Of course, good illustrations (or even animations) are not easy to create and require time and know-how. But again, if you really want to bring your message across, it's worth it – and in a pinch, any old napkin will do for a sketch board.

What to do

Having talked at length about why and how we want to communicate science, we should close with a brief look at what we can actually do. In our little workshop, we threw around several ideas that might be worth pursuing for us at the CCTB.

The two things we are already doing are my little blog here and the above-mentioned podcast. We also have a (mostly dormant) Twitter account that could be put to more active use. One of our number has been thinking about setting up a YouTube channel, that could be used to present the work we do, or to make Khan-Academy-style videos about computational biology available. The challenge with all of these is, of course, that every online channel needs at least one person who is dedicated to keeping them running, and who has the skills necessary to produce new content (especially for the videos).

But aside from the web-based communication, one shouldn't forget the offline world. Events to communicate science can be one-off, and have the potential of reaching local people who'd never stumble across any YouTube or Twitter channel we might set up. For example, we could participate in a Science Slam. Or we could organise a panel discussion on a science-related current-affairs topic, such as the “Fridays for Future” movement or the Insect Dying. (This is something I find really important to do, and would love to get involved with!) Other ideas we had were “Science in a Pub” evenings, or inviting school classes to our institute.

So you see, there really is a lot we could do, and quite a few things we perhaps ought to do. But what will we do? That, after all, is the essence. Communicating science is an art, a challenge, and a necessity. How will we go about it?

- - -

Further reading: Carsten Rahbeck from the Natural History Museum of Denmark, on communicating with the media.

Randall Munroe, xkcd.com

Tagged as science, writing, biology, society, essay, favourites