The Map of Power

Written on 2020-07-21

What is power? Why are some people more powerful than others, and how did they get there? What does it take to develop power? And if you can, should you—because isn't power evil?

Over the past few years, I have thought at length about leadership; what it is, and how to be effective at it. Power is one issue that you cannot avoid in this context. Leaders are powerful people. But what does that mean? And what consequences does this have?

Defining the power map

For the sake of this essay, I will define power as “the ability to get others to carry out your ideas”. Nobody will dispute that this is a trait that is very unequally distributed among humans.

One could imagine this distribution of power as an arrow, pointing from a galley slave (or his modern-day contemporary) to what we might call the “ideal dictator”, a single (hypothetical) person in total control of the entire world. But while the extremes of this arrow are easy to anchor, arranging the rest of the human race along it is not quite as simple. Who is more powerful: the parents of a medium-sized family, or the captain of a football team? A judge or a member of parliament? A military officer in charge of a hundred men, or a business executive responsible for a thousand?

A first (rather obvious) observation is that power is strongly context-dependent. I may be the bully on the school playground, but I'm still my father's son when I get home. I may be the father at home, but at work I still have to do as my manager says. While there is a strong autocorrelation (many powerful people are powerful in multiple settings), few people are equally powerful across the board of social contexts.

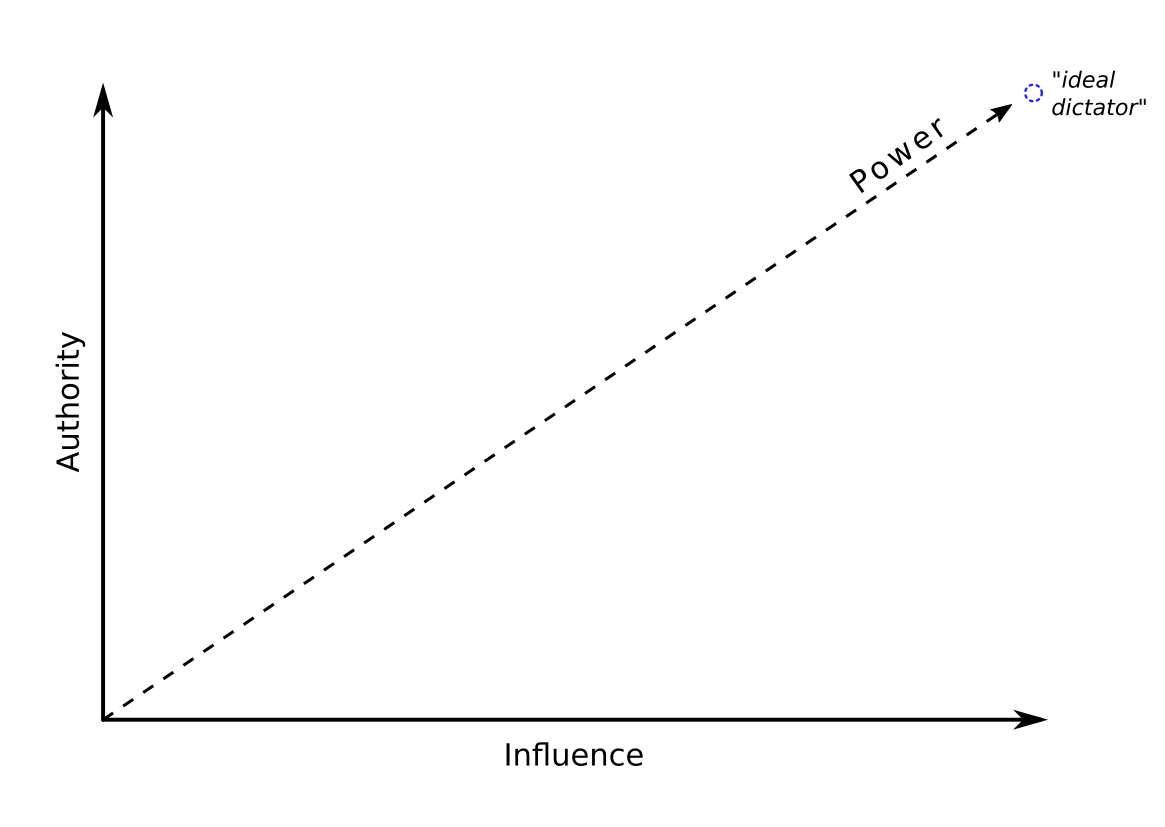

The second (and more interesting) observation, however, is that power is multi-dimensional. Indeed, I would like to posit that our “power arrow” is actually a two-dimensional vector combining the axes of “authority” and “influence”:

What do I mean by that? I mean that power can increase in two directions. I can get better at persuading people to do as I want, or I can persuade more people to do as I want. The first is authority: “How strongly can I motivate people to carry out my ideas?” The second is influence: “How many people can I reach with my ideas?”

And this is a really interesting concept, because when we think more deeply about what constitutes authority and influence, we begin to understand how power actually works.

Influence

Let's begin with influence, because this is a little simpler. In a sense it is nothing more than the number of people you are in contact with. To be precise, it is the number of people whom you can try to persuade to follow your ideas; or the social reach over which you can apply your authority.

This is a function of whom you know and how you communicate. Some people are influential because they seem to know everybody—no matter what problem you have, they'll know somebody who can help. Effectively, though, there is a limit to how many people a single person can really know. But that doesn't matter much, as long as you know the right people: people who are powerful, and who, in turn, know other people. That is why networks become increasingly important the higher up the ladder you climb. The more difficult the problems become that you have to deal with, the more important it is to be able to leverage the skills and resources of a wide range of people to help you. The old saying “Whom you know is as important as what you know” may sound a bit cynical, but it's true.

Building a network like that takes time, but depending on what your goal is, there may be a shortcut. Clever use of mass-media (no matter whether paper books or Facebook) can allow you to reach a vast number of people with comparatively little effort. The amount of authority you can exert at a distance is limited (we'll get to that in a minute), but you can certainly develop your own form of power. We even have a name for such people: we call them “thought leaders”, or, in newspeak, “influencers”.

Authority

Now for the “authority” bit—what is the strongest motivation you can offer someone so they do as you want? I think there are two main avenues you can use here: respect and fear.

Respect is an important asset for a leader. People follow a leader they respect, and they actively undermine one they don't. Although respect isn't tangible, it can translate to very real power—as Granny Weatherwax says, it's a “rock-hard currency”. But what is it that people respect? A few things come to mind:

Position. This is not as important as people like to think—just because you're “the boss” doesn't mean everybody will respect you. But a title does tend to help.

Character. Do people like you? Do they trust you? Do they believe that you really care about them and their needs?

Eloquence. Can you persuade people that your ideas make sense? Can you move them with your words and stir them to action?

Expertise. Do you actually know what you're talking about? Can people trust you to get the facts straight, or to execute a difficult operation successfully?

Experience. How long have you been in the game? Are you taking this road because you know the others don't work, or because this was the first thing that came to mind? Can you deal with difficulties and keep calm while doing so?

All these are components of what is often called “soft power”. Fear, on the other hand, is the driver of “hard power”. It is motivated by the threat of sanction, or even the threat of force. Hard power says, “If you don't do what I say, you will [pay a fine/lose your job/go to jail/be beaten/be killed].”

Although this sounds harsh, and modern Western culture tends to vilify such “extrinsic motivations”, there is a place and a time for them too. For example, parents sometimes need to use appropriate punishments to reign in wayward kids, and the government has to keep the peace—if need be, with force. The most effective leadership will usually end up using both forms of motivation, depending on the circumstances.

Exploring the power map

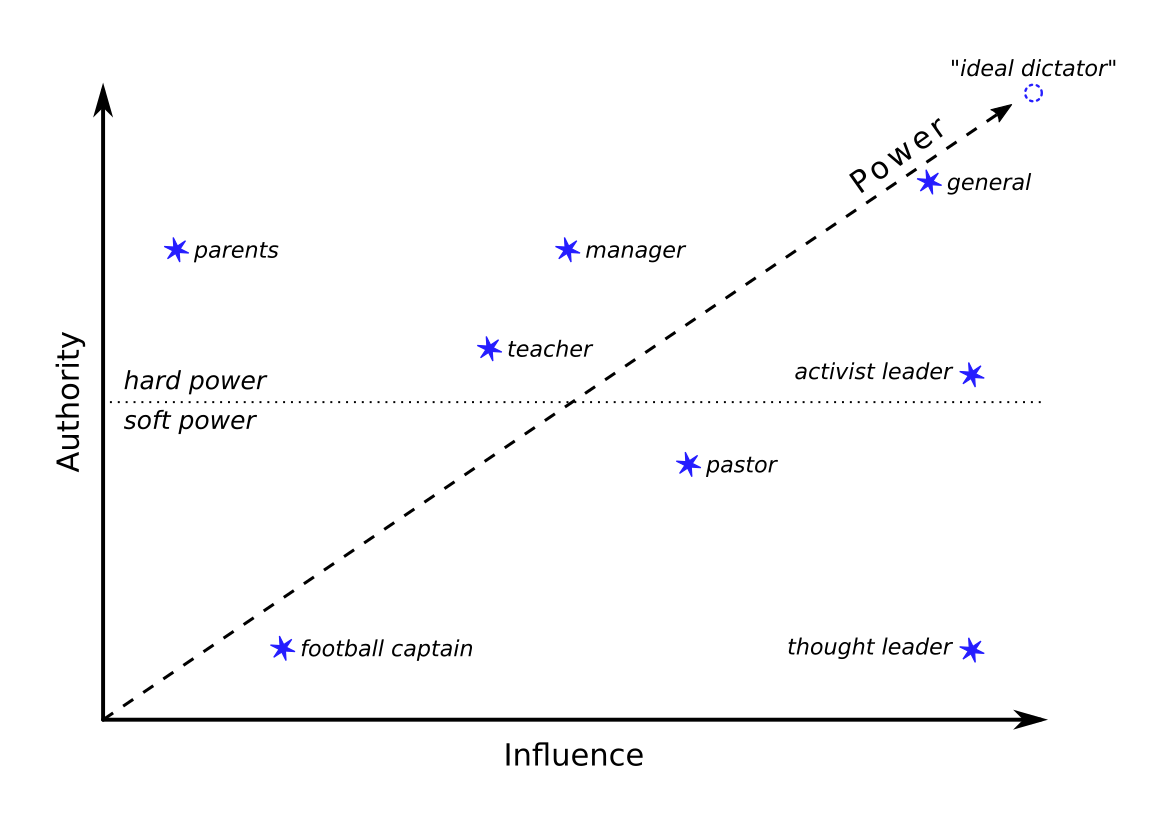

Having looked at the two axes of power, let us now take a look at a few examples of where different leadership positions fall in this coordinate system:

The football captain. Has limited influence (ten other players) and not too much authority, either. His authority mainly rests on his expertise, with some boost from his position and experience. But he cannot directly exert a threat of sanction, so he remains in the soft power domain.

Parents. Have very limited influence (their children). They do, however, have significant authority, both in terms of soft (due to age and experience) and hard power, although of course their ability to punish decreases as their children get older. (Note that parental authority is actually set in law.)

Teacher. Medium influence over a few dozen pupils. Medium authority based on respect (age, expertise, position) and threat of sanction (bad grades, minor punishments).

Manager at a mid-sized company. Medium influence (a few dozen to a few hundred employees). High authority, as firing is a significant threat of sanction.

Church pastor. Medium to high influence (between a few dozen and a few thousand members, depending on the church size). Medium authority, almost exclusively based on respect.

Thought leader. Somebody like Richard Dawkins or Rachel Carson. Low authority that is almost exclusively based on expertise and eloquence, but a very high influence (up to millions of readers).

Activist leader. High or very high influence (thousands to millions) from a large and well-structured network. Medium authority based mostly on respect, though the threat of sanction or force can be applied to outsiders (“If you don't do XYZ, we'll [launch a protest/boycott/go on strike]”).

General. Very high influence (several thousand troops) and very high authority (depending on the military jurisdiction, the threat of sanction reaches up to court martial or even execution).

Consequences of the power map

All right, now that we have thought about how power works, and seen that leadership positions differ in how they can exert power, let's take a look at some practical implications of this. First, we'll consider the perspective of a leader who wants or needs to grow his power. Then, we'll switch to a societal perspective and ask how these insights influence our democratic political system.

Power in leadership

As a leader, growing in power means increasing in authority and/or influence. The immediate corollary of this is that if you're constrained in one axis, you need to push on the other one.

We see this, tragically, with many dictators. If they come to power in a popular revolution, they will start off with a huge amount of influence. Over time, however, this starts to decay as the general populace becomes increasingly disgruntled. As this progresses, the dictator almost always tries to compensate by exerting ever more authority over his remaining followers. He escalates threat levels: the threat of sanction gives way to a threat of physical force and, ultimately, the threat of lethal force. In the end game, shortly before he is deposed, we have a manic paranoid ready to shoot anyone who doesn't obey him. But it's too late, his circle of influence is already too small.

On a more positive note, the vast majority of leaders are strongly limited in the amount of authority (and especially hard power) they can exert. A football captain usually cannot fire a team member; a manager cannot send anyone to jail. They can work on their soft power: they can become better at what they do, they can polish their speaking skills, they will almost automatically increase in experience.

Still, the quickest way to grow your power is to grow your network. This is not to argue that you shouldn't work on your proficiency—oftentimes, it is precisely your proficiency that will open the doors to new and valuable connections. But if you find yourself in a position with limited authority, where you nonetheless need to project power to accomplish your aims, you have to grow your influence.

The classic example here is activism. Political activists want to change social reality (such as abolishing slavery or implementing climate protection measures), but they do not have the authority to enact this change themselves. Accordingly, they have to persuade those who do have that authority; in short, they have to project power. Unfortunately, gaining hard power in a democracy is, well, hard. Until a sizeable portion of the population is behind you, you have to rely on soft power and influence.

This means the hard slog: gaining credibility, establishing a reputation as a knowledgeable source, arguing your case persuasively. But, crucially, it also means building your network and leveraging your connections. Which other groups share your goals and might cooperate with you? Which experts will support your statements? Which politicians might be favourable to your cause? And, of course: gathering new supporters. Because in the end, if you fail to reach your goal with soft power, the only way to exert hard power as a citizen in a democracy is to have enough other citizens on your side to vote your opponents out of office. Either way, relationship networks are decisive.

Power in politics

And now we are already in the midst of the political aspects of this topic. In a democracy, we say that “power is vested in the people”. What we actually mean is that the real authority never lies with an individual, but with the collective, with the state.

The state (i.e. the collective of citizens) is, in one sense, nearly all-powerful within its own borders. It can declare its will and develop ideas by passing laws. To get people to follow these laws, it can apply any threat of sanction or force it deems necessary.

But the key point is: it is the state that is wielding this authority, not any one person. How powerful is a judge? Well, he has the authority to send you to jail, or punish you in some other way. But he doesn't get to choose what behaviour merits punishment; he is confined to interpreting a body of law created by others. In short, it's not his will that he's enforcing at all. How powerful is a member of parliament? Well, he gets to write the law. But he has to get his fellow MPs to agree with him in order to pass it, and if the Supreme Court is suspicious they can strike it down, and if the people don't like it they can vote him out of office.

Basically, the whole point of democracy and the separation of powers is to limit the maximum authority any one person can possibly have. Unlike our dictator from the example above, anyone who's politically active in a democracy has their authority limited by the constitution. And this is a very good idea, because power corrupts and you do not ever want to have to trust anybody with complete authority. (We'll get to that in the last part.)

But the upshot of this is a direct application of the principle we saw above: if your power is limited on one axis, grow in the other one. In other words, influence is the true measure of power in a democracy, not authority. Decisions are made by a lot of people agreeing, not a single person decreeing. So if you want to influence decisions, you have to develop influence with a lot of people.

- In democracies, ultimate authority is vested in the state, never in a person!

- The point of “separation of powers” is to reduce the amount of authority resting on any one person, and transfer it to the collective

- decisions are made based on influence (a lot of people agreeing), not authority (one person decreeing)

- politicians need a lot of influence, but don't actually have that much authority

The ethics of power

Relationships and networks are really important!

that's the way humans (and human societies) work

Power is dangerous to individuals, but necessary for causes → power should serve others, not yourself!

Power is always there in any group of humans—the question is only who uses it and how

Stefan Kiechle, a Jesuit theologian, writes:

He who exerts power must be aware of and accept its ambivalence. With fear and trembling he will employ his power, knowing well that he is always in danger of abusing it. He will reflect on and reform his intentions. In close communion with God he will inspect his conscience and pray for good decisions.

Literature

Three books I recommend for further reading are:

John C. Maxwell, “The 21 irrefutable laws of leadership”, because it's hands-down the best book on leadership I know, and his central premise that “leadership is influence” has become a core tenet of my thinking on the subject.

Stanley McChrystal, “Leaders—Myth and Reality”, because this former general does an excellent job of portraying the myriad different ways different leaders project power, both via authority and via influence.

Stefan Kiechle, “Macht ausüben”, for a treatment of the ethics of power from a Christian perspective.

Tagged as leadership, politics, essay