Termites - African Engineers

Written on 2019-05-20

I've been around termites all my life – their tall mounds and annoying habit of chewing books were a constant companion of life in Zambia. I always found them moderately interesting: their mounds are impressive, but usually I saw them as little more than a source of food for my perennial favourites, the ants. This week, however, I read a paper that showed me a little bit more about just how cool these little critters actually are.

The paper in question is Sileshi & Arshad (2012), and deals with the question of how termite mounds affect their abiotic and biotic surroundings (i.e. both their non-living environment and other living organisms).

Mound building 101

First, some basics about termites and their mounds. Termites, it is important to note, are not ants (even though we always used to call termite mounds “ant hills”). Taxonomically, ants belong to the Hymenoptera along with bees and wasps, while termites are a completely separate group called the Isoptera. However, ants and termites are similar in that they are both social insects that form large colonies.

Not all termites build mounds. Whether they do and what shape that mound takes depends largely on which genus they belong to. The biggest mounds are those built by Macrotermes, which frequently reach 5m in height and 10m or more in diameter:

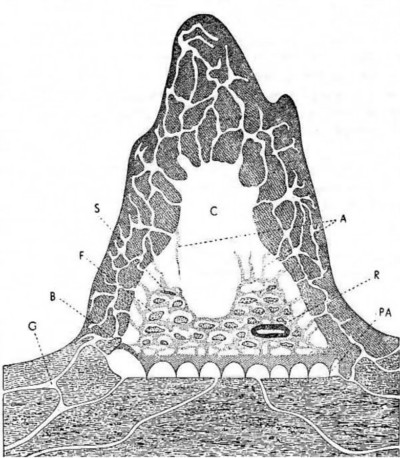

These mounds are masterworks of engineering. Their inhabitants live off fungi that they grow on dead plant matter, and the mounds are exquisitely designed to provide the optimal temperature, moisture, and gas regulation:

Sandias A. (1893), public domain

Apart from their function as high-tech greenhouses, they also have facilities for breeding and defence – a veritable city state in miniature.

Other termite genera build mounds in other shapes, such as these (which I am pretty sure are Odontotermes chimney mounds):

Beyond the mound

Now to the paper itself. All of the above information about the mounds themselves I already knew. What I hadn't yet realised is that they actually have a big influence on the surrounding landscape, too.

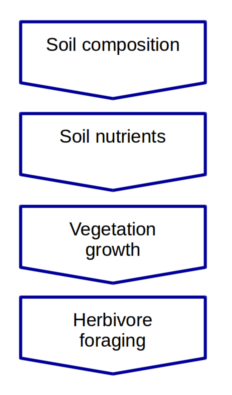

In investigating this influence, Sileshi & Arshad propose the following chain of causality:

Basically, they say, termites bring up a lot of nutritious, clay-rich soil from underground as they construct their mounds. (In fact, termite mounds contain so much clay and are so durable that we used them for fixing roads.) This soil turnover and the associated nutrient boost promote plant growth, which in turn means that animals find more food when grazing on mounds.

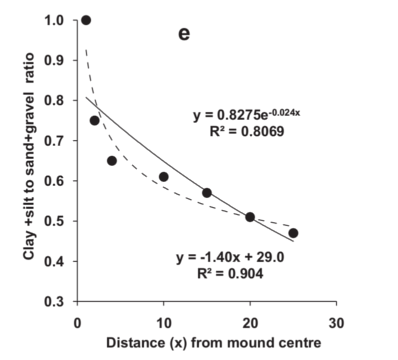

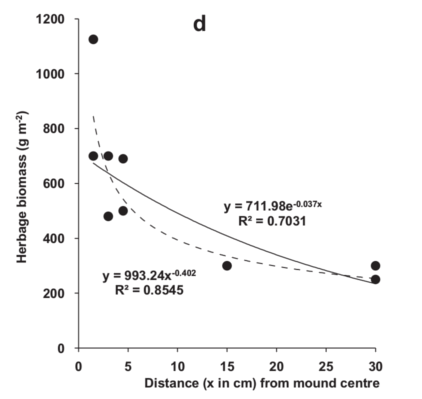

The authors' second prediction is that this effect decreases exponentially with the distance from the mound – i.e. the further away you are, the less soil turnover there has been. The effect of this would be to make termite mounds little “nutrient islands” in the landscape. And indeed, most of the data they analysed supported this hypothesis too:

When I read this, I was surprised at first, but then realised that I could have noticed this much earlier: as you can see in the first picture above, termite mounds virtually always have trees and shrubs growing on them, and are often conspicuous for their lush vegetation. (In fact, I had partly noticed this before, but didn't have any explanation for it. Glad to have found one now!)

Conclusion

Taken together, this shows how tiny, seemingly insignificant termites actually form the very landscape they live on. The years and decades that go into the building of a mound end up influencing not just the plants that grow in the area, but many of the larger animals too – grazers such as zebra, eland, or cattle. No wonder we call termites ecosystem engineers!